Building in Wetlands: Climate Challenges and Sustainable Construction Solutions

As climate change intensifies and urbanization pressures mount, cities across the Global South face a complex challenge: accommodating growing populations in safe and sustainable housing. In many urban areas like Accra, Ghana, land scarcity has pushed development into marginal spaces such as wetlands and flood-prone valleys. Climate change has exacerbated the impacts of flooding and waterlogging on buildings, especially in urbanized wetland zones (Adinyira et al., 2024). While these areas are increasingly being converted into residential estates, the consequences of such unplanned urban expansion, rising dampness, structural degradation, and public health risks demand urgent, sustainable engineering responses.

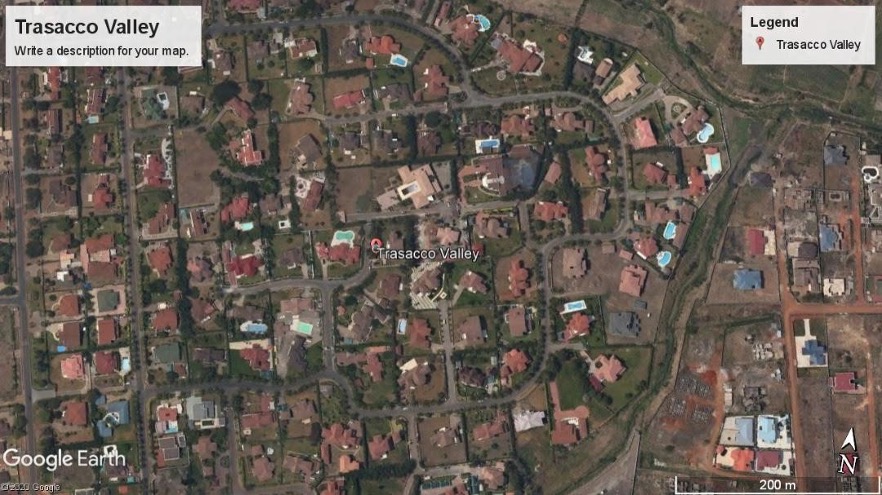

The construction of homes in waterlogged environments reveals the intersection of urban planning failures, climate vulnerability, and the urgent need for adaptive building practices. In areas such as Trassaco Valley, a high-end residential enclave in Accra, buildings are routinely affected by water-induced damage: damp walls, cracking structures, peeling paints, fungal growth, and salt-induced corrosion. These are not merely cosmetic problems, they pose serious structural and health risks, often exacerbated by inadequate drainage systems, poor soil preparation, and substandard materials.

Figure 2

|  |

From a sustainability perspective, building on wetlands disrupts vital ecological services such as groundwater recharge, flood buffering, and carbon sequestration. Wetlands serve as natural climate regulators, and their conversion for urban development compromises both biodiversity and the resilience of communities to climate-induced disasters. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021), cities that expand into ecologically sensitive zones without adequate safeguards will face heightened risks from extreme weather events, particularly flooding and erosion.

However, innovative solutions are emerging—rooted in rethinking materials, techniques, and policy frameworks for construction in climate-sensitive zones. Research and fieldwork in Accra indicate that the use of damp-proof membranes (DPM), waterproof cement, and chemical sealants such as Oxah-HXL+W and RD2-Green can significantly reduce water ingress and enhance structural resilience. Additionally, installing weeping pipes—perforated PVC channels laid during foundation work can redirect groundwater away from buildings, preventing capillary rise and the resulting dampness. These practices align with climate-resilient architecture principles, which prioritize passive drainage, soil remediation, and water-resistant materials as the foundation of sustainable design (UNEP, 2022).

Foundational preparation is equally critical. In areas with high water tables, replacing loose, moisture-laden topsoil with compacted lateritic fills improves load-bearing capacity and reduces ground saturation. Proper drainage infrastructure must be integrated at both plot and community levels to eliminate the unethical and dangerous practice of redirecting water to neighboring properties an act that undermines both climate justice and public safety.

Community interviews and surveys conducted in Accra reveal that many residents are aware of the dangers of building in waterlogged zones, development often proceeds due to proximity to the city or a lack of viable alternatives. This reflects a deeper policy gap in spatial urban planning and housing regulation. To address this, governments and urban planning authorities must enforce stricter building codes for wetlands while providing incentives for sustainable construction through subsidies, tax breaks, or technical assistance.

Health implications further emphasize the urgency of the issue. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) reports that damp indoor environments contribute to respiratory infections, asthma, skin irritation, and other health issues particularly among children and the elderly. Thus, sustainable housing in wetland areas is not only a structural challenge but a public health and equity imperative.

Ultimately, building in wetlands is not merely a question of technical adaptation, it demands a holistic, multi sectoral response. It requires material innovation, responsive policy reform, and inclusive public education. As cities like Accra confront climate realities and rapid urban growth, housing solutions must prioritize resilience, equity, and environmental stewardship. Building for the future means building with nature, not against it.

“We shape our buildings; thereafter, they shape us.” — Winston Churchill

Written by : Samuel Osei-Amponsah.

References

1. Adinyira, E., Amoako, C., Kwofie, T. E., Aigbavboa, C., Agyekum, K., & Addy, M. (2024). Resilient infrastructure development in Africa’s changing climate. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-69606-0

2. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

3. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2022). A practical guide to climate-resilient buildings. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/practical-guide-climate-resilient-buildings

4. World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Guidelines on indoor air quality: Dampness and mould. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789289041683

Comments

No comments available.